SO Large Aperture Telescope

What is the SO Large Aperture Telescope?

The SO Large Aperture Telescope (LAT) is a 6m Crossed Dragone Telescope that provides a high-resolution view of the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB). The defining characteristic of the Crossed Dragone telescope is its large secondary mirror, 5.9 meters in diameter, nearly the same size as the primary mirror.

Figure 01 is a rendered cross section of the LAT, with the primary and secondary mirrors labeled. This enormous secondary gives the LAT an unprecedented 7.8⁰ field-of-view (FoV), which means that the LAT can observe large portions of the night sky at once, which in turn means it can survey the sky rapidly.

To take advantage of this large FoV, the LAT is equipped with the 2.4 meter diameter Large Aperture Telescope Receiver (LATR), the largest of its kind. The LATR is essentially a camera.

Unlike a camera you might have at home, the LATR needs to be cooled to 0.1K, just a hair above absolute zero, to work. To achieve these frigid temperatures, the LATR uses a layer-cake design, with progressively colder stages insulating those below them from the heat.

To reach these temperatures, the entire LATR is a vacuum chamber with 13 windows cut in the front to allow light from the sky to reach the detectors by way of the LAT mirrors.

Figure 02 shows the LAT as actually constructed, while Figure 03 shows the inside of the LATR with a portion of the LATR team.

Starting with the room temperature vacuum shell, fiberglass struts support a 40K stage, which surrounds the remaining stages. A similar support mechanism suspends the 4K stage from the 40K.

These two stages are wrapped in highly reflective multi-layer insulation, the same used on spacecraft, to protect the colder stages from radiation from the vacuum shell. The 40 and 4K stages also contain optical filters which reject unwanted light from the sky.

Unwanted light is light from outside our frequency range of interest which would only serve to heat the LATR. Both the 40 and 4K stages are cooled by pulse tubes (PTs), which function very similarly to your refrigerator at home, but use pure helium as the refrigerant gas. A cut away of the LATR is shown in Figure 04, with the major components labeled.

Below 4K, the LATR branches into 13 optics tubes (OTs), which are attached to the 4K stage and which contain the 1K and 0.1K (or 100mK) stages. A cut away of an OT is shown in Figure 05.

The LATR is sensitive to six bands of light, ranging from 30 to 300GHz. Splitting the spectrum into six bands enables us to separate our signal of interest, the CMB, from contaminants, such as gas in our galaxy.

Each frequency band, however, requires different optical elements such as filters and lens; as such, detectors are distributed across several OTs which have different optical elements. Adjacent frequency bands can share optical elements, so we end up with three types of OTs for our six bands: low, mid, and high frequency (LF, MF, and HF).

Each OT starts at 4K, and progresses to 1K and 100mK, with the stages separated by carbon fiber supports. The 100mK stage is the coldest stage, and it is where the detectors live.

From there, each of our 30, soon to be 60, thousand detectors look out, through the filters and lenses of the OT, through the filters at 4 and 40K, through the room temperature window, bouncing off the secondary and then the primary, out to outer space.

The 1K and 100mK stages are cooled by a dilution refrigerator (DR), the same type of refrigerator used to cool quantum computers. A picture of the DR as installed in the LATR is shown in Figure 06.

The DR works by diluting the helium isotope He-3 in a mixture of He-3 and He-4. This process is endothermic, i.e. it requires energy, down to arbitrarily low temperatures. Thus, the DR can provide cooling power down to nearly absolute zero, although its cooling power decreases with decreasing temperature.

We operate at 100mK, which offers a nice balance of cooling power and low temperature. We go through such great lengths to reach 100mK since our detectors need to be that cold to do their job.

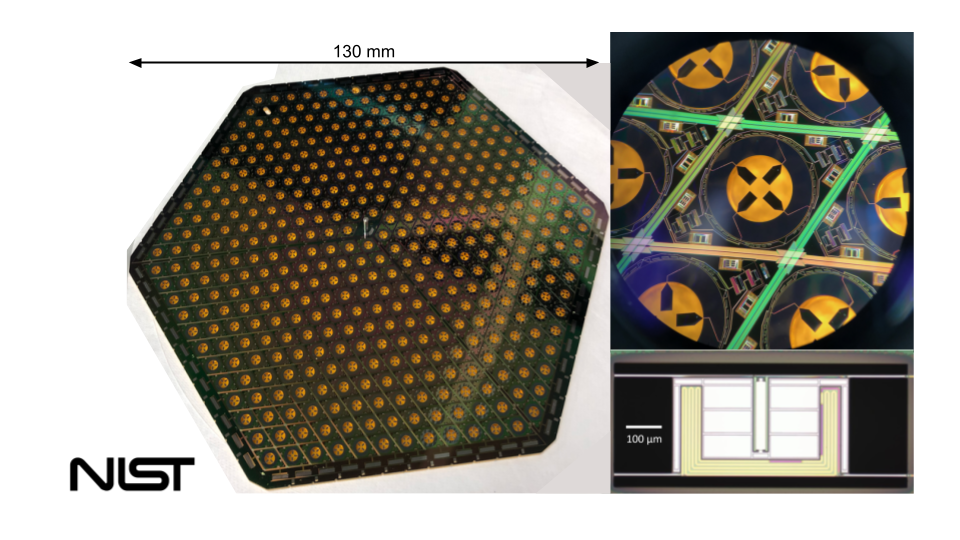

SO uses transition edge sensors (TESes) to detect incoming light. A picture of a TES array, as well as a close up of individual TESes, can be seen in Figure 07. TESes are essentially very sensitive thermometers, and they detect incident light by the heating that light causes.

Exactly as you are warmed by the sun on a bright day, our detectors are warmed by the CMB. The CMB is much, much dimmer than the sun, however, so our detectors need incredible sensitivity, less than 1mK. The upside of all this work is that our detectors are very close to the limit of how sensitive any one detector can be. If we want to make more sensitive measurements of the CMB, the only thing we can do is to add more detectors. This requirement, in turn motivates the huge size of our receiver.